There’s no such thing as not playing. Music has rests in it. So, you’re on a rest and the music will begin shortly.

Tom Waits, Fresh Air interview on NPR

If you’re interested in musicianship, aural skills, and ear training, most of the practice you do probably revolves around listening to sounds. Whether you use individual notes, chords, rhythmic parts, complex timbres, or practise active listening in real music, you probably spend your training time listening. As well you should!

But perhaps we’re forgetting a complementary part of developing our ears for music?

Claude Debussy said that music is in the space between the notes, and it’s important to remember that silence can be just as important as music.

Silent Adoration

In the midst of a week filled with all kinds of exciting music, most of it new to me, I went for the first time to an “adoration of the blessed sacrament” service. Though I was raised Catholic, this is a part of the Catholic tradition I’d never really come into contact with before. The service started with some prayers spoken together, the sacrament was presented at the altar, and then for the rest of about an hour we simply knelt and prayed. In silence.

This was a marked change from the rest of the services during the week which were lively, musical and generally full of youthful exuberance. We simply knelt, and prayed, in silence.

That’s not to say that the world was silent around us.

Though the chapel stayed quiet, we were in the midst of a busy dorm building, and there was chatter from time to time, along with some feint noise from the street. It became a particular task to focus on the silence, guarding against these distractions, and I was reminded of two interesting and useful approaches to nurturing inner silence and quieting both inner thoughts and sounds from the outside world.

Quieting the Monkey Mind

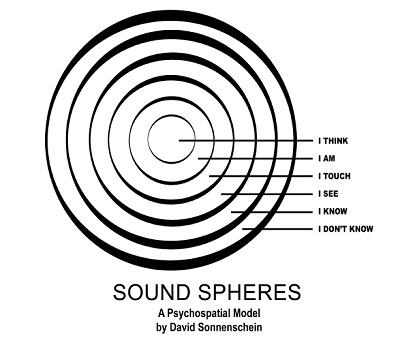

David Sonnenschein presents a model of “sound spheres”, a way of representing all the different kinds of sounds we experience every day and the different ways they impact on our mind:

The levels he defines range from the most distant sound at the furthest level “I don’t know” to the closest, most intimate at level “I think”.

I think the outermost two levels of this model, “I know” and “I don’t know” are perhaps the most interesting. They represent sounds that you perceive but whose source you can’t see. The “I know” level is for sounds where you immediately know the cause, where your brain automatically constructs the obvious explanation for what you’ve heard. In the outermost level, “I don’t know”, our brain does not (or cannot) have an explanation of what caused those sounds. So unlike the meiow of a cat outside, for which your brain instantly constructs the explanation “there is a cat outside”, some sounds defy instant classification and so do not quite become a part of our mental model of the world around us.

In his book “Meditation for Beginners”, Jack Kornfield writes guidance on how during vipassana (mindfulness) meditation it is important not to try to block out sounds completely; but neither to let yourself become distracted by them. He offers a helpful approach: allow the sounds to impact upon your ear, but to go no further. Let yourself be aware “there is sound hitting my ears” but try to curtail your thoughts before they rush off to categorise, analyse, or explain the sound:

When you become aware that you are listening to some noise in your environment, you can include that listening in your awareness in the same way that you pay attention to the sensations in your body. You can simply feel the sound as it touches your ear, and you can note, if you wish, “hearing, hearing, hearing.” You can let the sound be a wave, just like the breath is a wave. When the sound passes, then you can return naturally back to the breath.

Essentially he’s advising that you try to keep the sounds abstract, to keep them in a domain where they can be more easily dismissed than when they have been connected to an explanatory mental model.

Abstract Sounds Across the Spectrum

This is particularly interesting guidance for somebody who’s been doing ear training for audio bands and EQ. In that training you are very much learning to disassociate from a lot of the instinctive analysis your brain does on sound, to allow you to listen in a more abstract way. Rather than hearing “drums + guitar + bass guitar” you in a sense relax your ears and try to hear the sound as a whole – and then listen for its presence in various parts of the audio spectrum. Thus dissolving the neat classification-by-instrument model your brain has constructed, so that you can listen in a different way.

To some extent this kind of training makes it easier to avoid distraction by sounds, as you can relax your ears, avoid that automatic mental modelling, and let the sounds slide off your ears without going any further. But in some ways it makes it more difficult because having refused to classify the sounds, you may find yourself automatically analysing them with your shiny new EQ skills! It may not be a cat’s meiow distracting you, but now it’s the 700Hz resonance of the room, or the way that repetitive sound in the background has three distinct frequency components to it…

An Ongoing Effort

For my part, I still have a way to go in learning to control my hearing. The techniques mentioned above have helped me, and in a time of quiet focus I can employ them quite effectively. But it will be a while yet before I feel able to use them to limit my mental response to unwanted sounds in more everyday situations, out in the normal world.

I believe this is a key part of developing one’s ear. It’s not enough to be expert in analysing all the sounds that you hear. One must also be in control of which sounds the brain spends effort on, and be able to disable that analytical inner ear when its continual instinctive and reactive modelling is unhelpful or unwanted.

Global and focal listening meditations also make us conscious of our extraordinary ability to filter sounds, as when we are in a room full of noise and focus in on one person’s voice. The ability to create “silence” selectively by focusing our listening is one of the greatest miracles of listening.

William Osborne on Pauline Oliveros’ Deep Listening

The practice is intended to expand consciousness to the whole space/time continuum of sound/silences. Deep Listening is a process that extends the listener to this continuum as well as to focus instantaneously on a single sound or sequences of sound/silence

My name's Christopher Sutton and this is my personal blog. You can learn more about me

My name's Christopher Sutton and this is my personal blog. You can learn more about me