The startup world loves “bootstrapping”: the idea that you get a business off the ground not by seeking investment and outside funding, but by starting to sell products or services and then gradually growing the business using your own income. It comes from the expression “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” and just means that you’re using whatever resources you have to hand to get yourself going. I’m a bootstrapping fan myself; it’s how I’m running Easy Ear Training so far.

Lately I’ve been thinking about bootstrapping in music learning, and specifically ear training.

There may not be an obvious connection to you, but if you’re a musician you’re probably doing this to some extent already – just without realising it!

There’s a huge wealth of history to music tuition, and no shortage of teachers to tell you “this is how you learn X”, “this is how you practise Y”. And I wouldn’t for a second want to dismiss the value there.

But there’s another way too. This is the attitude of bootstrapping. Of “do whatever works”.

Bootstrapping your music education

If you want to be a concert pianist or reach the top of the profession in your chosen instrument or talent, you need to be careful. You don’t want to learn the wrong fingering for a scale, or develop poor embouchure early on – because the more you practise the wrong method, the more ingrained it becomes, and the harder you have to work later on to fix it. As a saying I recently came across puts it: “Practise makes permanent”.

That suggests that a “do whatever works” mentality is wrong-headed, and will only cause you pain later on.

But I think that attitude is far too motivated by fear. Yes, there are cases where you’ll end up having to re-learn techniques later on, and it’s generally best to learn things right in the first place – but I believe far more musicians give up out of frustration than ever reach the stage of having to re-learn bad technique!

So what’s better: to progress and become a better musician with some bad habits, or to get bored trying for perfection and give up entirely?

Are bad habits really that dangerous that we should threaten our enjoyment of music for the sake of avoiding them? Let’s look at a few examples.

Example: Guitar chords

When I learned guitar, I was taught the “correct” way to finger an A major chord – with my second, third and fourth fingers – which (my teacher told me) would give me more fluidity when changing chords and make sure my fluency wasn’t limited by bad fingering later on. Now, when I see someone finger an A with their first, second and third fingers, I think it looks wrong, and somehow amateurish.

But you know what? They’re almost always better guitar players than me!

This realisation really hit home with me, and while I’m still glad I learned the “correct” fingering, I’m a lot less snobby about it than I used to be.

Example: Interval recognition

When learning to recognise intervals, a lot of students have difficulty distinguishing sixths and sevenths. They’re a big leap, and though you can learn to distinguish the major and minor variants just by the overall sound, it can be hard to tell, say, a minor sixth from a minor seventh.

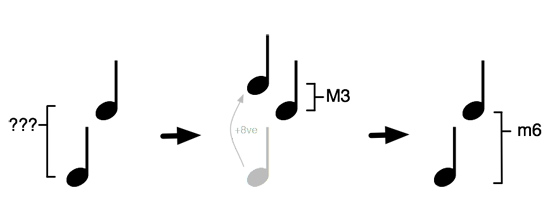

Want to know the trick? You get started by listening for the inversion. You may not know a minor sixth from a minor seventh, but you almost certainly know a tone from a major third. So you listen, and then sing (or in your head you auralise) one of the notes up or down an octave, transforming what you heard into the inversion.

At a glance, this method seems like a bad idea. In a real musical situation, you’re never going to have time to do these kinds of aural gymnastics to figure out the interval. So why derail your learning by using a self-limiting approach?

But guess what: the human brain is incredible.

While you’re jumping octaves and listening for the inversions, your ear will be getting more and more used to the sound of the interval. After a while, you’ll barely need to actually imagine the inversion, you’ll just get a sense of which inversion it is – you might begin to hear the inversion as part of the interval. Then, you’ll start to simply recognise the interval directly. This is because all the while, your brain has been getting more and more familiar with the interval, understanding the frequency components which make up the sounds, and setting up better pattern recognition for the interval itself.

So though it may seem like a mistake to use a method like this – it’s just bootstrapping, a way to get your brain started on recognising the intervals.

Note: The same principle holds for learning intervals with reference songs. It’s not a sustainable approach, but it’s a great way to start tuning in your ear!

Example: Learning new pieces

Suppose you’re a teenage piano player. You hear a song you love and naturally you want to play it on your instrument. You tell your teacher, they hunt down the sheet music, and next lesson you take a look.

And it’s horrendous, page after page of densely-packed notes, looking more like the classical pieces you were studying already than anything rock and roll. Suddenly your enthusiasm is sapped.

Most pop and rock sheet music is painfully literal in its transcription. Great if you want a note-perfect rendition of the song, next-to-useless for the enthusiastic novice who just wants to bash out a recognisable version of the song as soon as possible.

So what does the smart teacher do? They get you to read the melody line with your right hand, and play from the chord boxes with your left hand. Yes you’re ignoring the vast majority of the painstakingly-transcribed notes on the page, but almost immediately you’ve got a playable version of the song.

You get that burst of satisfaction and pleasure that comes from playing music you love – which might have taken hours of effort had you simply plodded through learning the sheet music note-by-note.

And here’s the crucial part, which turns this into bootstrapping rather than just half-assedness: Using the chord boxes and melody as a starting point, and powered by that burst of enthusiasm which playing a recognisable rendition will have produced, a skillful teacher can help you gradually move from the simple rendition to the sheet music version, by building on what you’re already playing.

I’m not saying anything ground-breaking here: simplifying an arrangement as a first step to learning it is a common approach. But there are also a lot of teachers (and hence musicians) who look down on that method, believing it counter-productive compared with slowly learning the full arrangement directly. And while that’s a valid approach too, I’d argue that it’s a more tedious, frustrating, and ultimately demoralising one compared with letting the student play music from the outset, and bootstrapping from there.

Bootstrapping Principles for Music

- Always try to find the correct method. But make your best informed guess, and then run with it. Don’t feel guilty for not having expert approval for your way of doing it.

- If you have a choice between a “cheaty” method, and a correct method, don’t pursue the correct method so much that it discourages you completely! It’s better to progress using a “cheaty” method and continue enjoying making music than it is to get frustrated and never make progress at all.

Note: This is of course a little different when teaching children, who tend to have a lower threshold for frustration! The principle still holds though. There’s no point drilling scales to the point where the child begins to hate his lessons. - If you see another musician doing something differently than you do, don’t be afraid to ask about it, and try doing it that way yourself. You may find they’ve discovered a shortcut which can help you leap ahead.

- As powerful a technique as bootstrapping is, don’t take the gung-ho attitude too far. Sometimes you must accept that a bad technique is holding you back, and put in the work to correct it. This is an important part of progressing as a musician, and though it’s not as fun as taking the bootstrapping shortcuts, it’s a sign that you’ve reached the next level in your musical development. So rather than resent it and put off fixing the problem, you should welcome it – as a new triumph in your learning.

By consciously using bootstrapping in your musical education you’ll find you can progress faster by making smart compromises between the standard “correct” methods and the methods that work best for you.

Have you used bootstrapping while learning your instrument? What are your favourite music education “hacks”? What’s helped you to progress even though you know it’s not the “approved” method?

Apologies if this post has left you, like me, with “These Boots Are Made for Walkin'” stuck in your head…

My name's Christopher Sutton and this is my personal blog. You can learn more about me

My name's Christopher Sutton and this is my personal blog. You can learn more about me